Biblical History

摘自 IVP New Dictionary of Biblical Theology

作者: P. E. Satterthwait

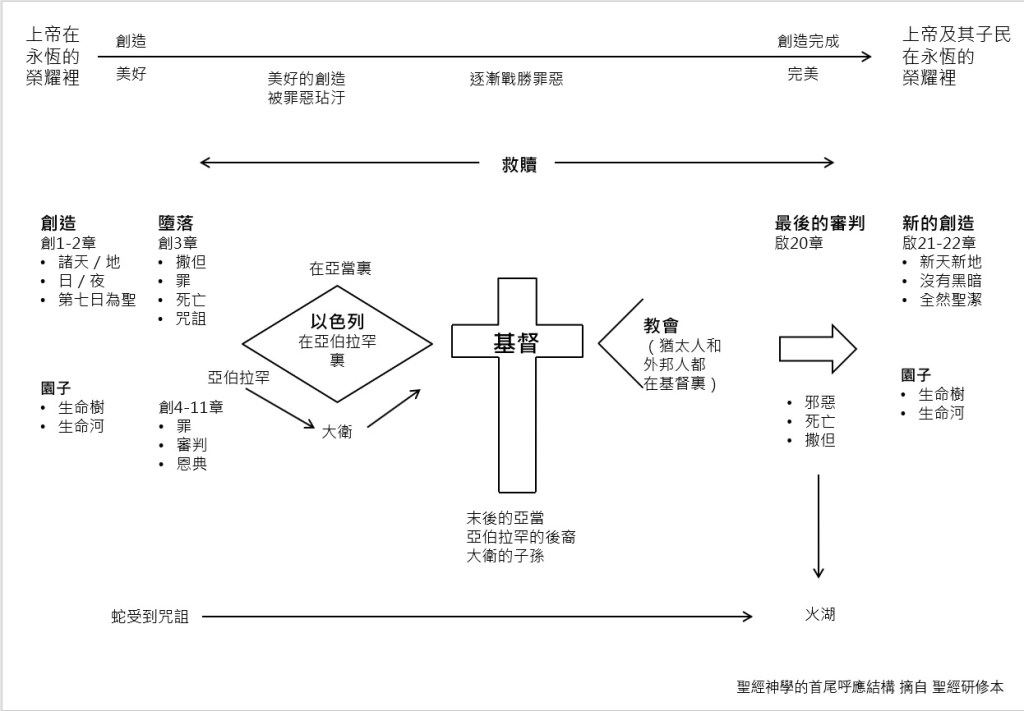

從創造到新創造

《舊約》

舊約聖經一開始所描述的是,上帝創造了世界,創造了一切有生命的活物,尤其是第一對男人和女人。他們蒙受上帝的祝福、受到上帝的委派、要以順服上帝意旨的姿態來管理這個世界(創一、二)。創世記三章至十一章所講述的,是這第一對男女對上帝的悖逆以及其種種後果。創世記十一章1至9節是這段故事的結束,故事結尾給我們留下的,就是一幅與我們現在所看到的世界非常相似的圖畫。在這幅圖畫裏,所有世人,無論男女,都與上帝隔絕,他們彼此也相互隔絕,無法自救。

但在講述人類如何遍滿全地時,聖經不僅僅是注重講到人類的邪惡蔓延到全地,也講到上帝把應許賜給了人類第一個女人(創三15),這要向我們顯示,她的子孫中將會出現把這個因邪惡而導致的毀壞性後果扭轉過來的「後代」(「後裔」一詞可以是指一個人,也可以是指眾多的子孫,其詞義具有一定的含糊性),而這個後代將會消除由罪惡帶來的各種毀滅性後果。

創世記三至十一章的家譜,就是在講這個應許的發展,那裏集中講到某一個後代的延伸,從亞當到塞特,再到挪亞和閃,這些人都與盼望、公義、祝福息息相關(創四25~26,五29,六9,九26~27)。後來又記載了一個家譜,把這一支派的後代一直延續到亞伯蘭(創十一10~26)。

在創世記十二章中,亞伯蘭蒙召離開他的本族、本地,並得到上帝給他的一個應許,說他的後裔將成為大國,他們不僅要自己蒙福,而且上帝還要透過他們,使「地上的萬族」(2至3節)都蒙福。從這一應許的條款中,我們隱約可以看到,創世記三至十一章所描述的那些負面的發展趨勢,將會被扭轉過來:有一個後裔將重新恢復上帝應許給首先的人的祝福(參見創一28),有一個國將要被上帝用來對付人類現在分散隔離、成為多國、多族的這個咒詛(參見創十一1-9)。這樣,在創世記第三至十一章與第十二章之間,就形成了一個「難題」與「解答」的關係。而摩西五經的其餘部分,講的就是這一應許如何部分地一一得到實現。

亞伯蘭的後裔在埃及成為了一個大族群(出一6~7),他們在《出埃及記》裏得以從被壓迫的奴役中拯救出來,並且通過摩西的中保工作,得以在西奈山上與上帝進入到一個聖約關係中,成為地上一個特殊的國家,即上帝的百姓以色列。他們將要認上帝為王,遵守祂的律法,以他們集體的生活反射出上帝的聖潔來,以此成為祭司,向萬國彰顯上帝的屬性,並且使萬國蒙福(出十九4~6,20~23;利十九1~2;參見申廿六17~19)。

《出埃及記》至《民數記》這幾卷書,則是從對以色列這個民族生活形象的描述,來反映出以色列與上帝的特殊關係。當他們紮營時,上帝在他們中間;當他們邁向應許之地時,上帝在他們前面行走。當來到《申命記》時,也是到了摩西向以色列民宣佈遺言訓示的時候,當時他們正要進入那片應許之地(申四1~2;比較創十五18~21)。

以色列民對應許之地的奪取過程始於約書亞的率領(書一~十二)。經過了後來幾代人在這片土地上所遭遇的種種困難後(《士師記》,特別參見二6 ~三6),整個對應許之地的征服,在以色列的第二任君王,即大衛,攻取耶路撒冷後,正式完成(撒下五6~10)。

由於大衛的登基作王,應驗了許多上帝給亞伯拉罕的應許,所以要給大衛一個應許,也是一件十分合宜的事了。於是,上帝應許他,以後凡坐在寶座上的王,都會由他的後裔而出。而這個應許的條款,也是與先前的應許相呼應的(撒下七9~16,特別參見12節;參見創十二7,十五4)。

大衛王與所羅門王在位的時期,以色列國在那片土地上安享了摩西所預期的「太平」(撒下七1;王上五3~4;參見申十二10)。上帝在以色列中作王這一事實,也彰顯在約櫃被搬到了耶路撒冷(撒下第六章),以及聖殿在耶路撒冷被建造起來(王上六~八章)這些事情上。這時,以色列開始受到鄰邦國家的仰慕,這同樣也是正如摩西所期盼的(撒下八8~9;王上五1~2、7,十1~9;比較申四5~8)。

從這時起,「坐在大衛寶座上的王」(對於這個王的另一個稱呼就是「彌賽亞」或「受膏者」;參見撒上二10)這個人物的形像,就變得非常重要了。例如,《詩篇》中許多的章節都對這個王之角色的重要性作出了許多的闡述,將之與上帝在錫安對萬國施行公義統治這個主題聯繫起來。

此後則是一段長期的衰落時期:從所羅門王對上帝不忠開始,導致了國家在他兒子羅波安繼位後分裂(王上十一~十二);接下來就是南北兩國越來越悖逆上帝(王上十六;王下,特別參見十六章,廿一章;何四~五;耶二~三);然後就是這聖約的詛咒(申廿八章)應驗在外敵對南北兩國的入侵(王上十四25~26;王下五1~2,十32~33,十五29,廿四1~2)、圍城與饑荒(王下六24~25,十七5,廿五1~3)以致最後,兩個王國分別被擄到亞述和巴比倫(王下十七6~23,廿五11)這些事情上。耶路撒冷的聖殿被毀,這時上帝的榮耀早已離開了聖殿,因為它已經被上帝的百姓所玷污(王下廿五9;結八~十)。

先知書中記載了審判將至的警告,同時也包括對審判之後必要來臨之復興的預言:那裏講到上帝必會赦免祂那些願意回轉悔改的百姓(何二;耶卅一18~20;比較申卅1~10;王上八46~51);講到兩國必會合二為一,居住在得潔淨的土地上(賽十一11~16;耶三18,卅1~11;結卅七15~23,四十八1~29),並且得著能力,以一種全新的方式順服上帝(耶卅一31~34;結十一16~21;番三9~13);講到耶路撒冷和聖殿必會被重建起來(賽五十四;耶卅三1~13;結四十 ~ 四十三),上帝必會再度居住在聖殿中(結四十三1~4,四十八30~35);講到將來必有一位君王要從大衛的支派出來,以公平治理百姓(何三5;賽十一1~9;彌五1~5;耶廿三1~6;結卅七24~28);講到將來萬國都要聚集到錫安,要認識以色列上帝的道(賽二1~4;耶三17);最後還講到,整個創造界必會恢復原貌,正如以西結在異象中所見到的那樣,有一條河從聖殿流出,讓死海的水得以活過來(四十七1~2),或者像以賽亞在異象中見到的新天新地那樣(六十五17~25)。

對以色列國復興的描述,有時候用的幾乎是跟描寫復活的語言(比喻式地)一樣(結卅七1~14;比較何六1~3)。在此需要著重強調的一點是,以色列的復興被視為是一幅更大圖畫的一部分,那就是整個受造界的更新,以及萬國得福,對上帝呼召亞伯拉罕之目的的實現。

對於這個復興的預言,先知書中一段最長的經文,要數《以賽亞書》40至55章了。這段預言中引介出了一個被稱為「(主的)僕人」的人物(賽四十二1,四十九5~6),他在某種意義上取代了以色列的角色(以下這幾章裏,也以「僕人」一詞來指稱他:四十一8~10,四十五4)。這人是為見證上帝的大能而來的(四十三10-13),即當那些活在悲慘的被擄生活中的以色列民太軟弱或太頑梗,無法完成這項見證上帝大能的任務時(四十二18~25,四十八1-11),他來了。這一思想在四十九章3至6節中尤為突出。在這些段落裏,這位「僕人」以第一人稱宣佈,上帝對他說:「你是我的僕人以色列」(3節),而他受差遣的任務,是既要向被擄中的以色列傳講信息(5節),又要成為「外邦人的光」(6節)。有關這位僕人的經文,最讓人震驚的一段說到,他將會替上帝百姓的罪受死(五十三5~6、8、11~12),其所用的語言,不禁讓人想起《利未記》關乎到獻祭的經文。這人的身分並不確定,而且這還不僅僅是由於文中沒有道出他的名字之故而已。他在某些方面,像個君王或者先知,還在許多地方與摩西相似,尤其是《民數記》裏所描述的摩西。無論如何,他的角色基本上來說,都是前所未有的。《以賽亞書》四十九至五十五章所描寫的時間段也不是很清楚,這些章節似乎講論著一個超出被擄回歸的時期,而且延伸到一個錫安的榮耀完全被恢復的未來時期(五十四章),並且這位僕人的事工與受死的時間,也可能就在這個遙遠的未來。

《以斯拉記》與《尼希米記》兩本書,記錄了接下來具體發生了些什麼事:波斯王居魯士擊敗巴比倫後,允許從南國被擄來的猶太人及其後代歸回猶大地(拉一1~4);他們當中許多人也確實回到了猶大地,重建了聖殿,再次在猶大地過逾越節(拉三,六13~22);在尼希米的帶領下,耶路撒冷的城牆在面對敵人四面攻擊的情況下得以重建(尼三~四、六);耶路撒冷城終於再度有人居住了(尼十一)。城牆落成後,眾人舉行獻城牆禮,歡天喜地地慶祝(尼十二27~43)。這些都是重大成就。然而,在這些書卷中,依然蕩漾著一種渴望與失望的調調。在《尼希米記》八至十章所描述獻城牆禮的中段,有一個很長的認罪禱告(九章),而那個禱告則是以以色列民為他們當下的處境哀痛作結束的。他們現在在上帝賜給他們祖先的土地上仍舊為奴(36節),受外族君王的轄制,「遭了大難」(37節)。而《以斯拉記》與《尼希米記》兩卷書的最後幾章,都說到一些被擄回歸的人如何又陷入罪中:如不守安息日(尼十三15~22)、不繳納什一奉獻(尼十三10~13),更嚴重的是,他們娶了非以色列民的外族女子為妻(拉九~十;尼十三23~28)。很明顯,《以斯拉記》與《尼希米記》裏所描述的事,跟論及「復興」的那些預言所表達的期望,相去甚遠。

每一卷被擄歸回後時代的先知書,在結束時都以不同的方式重申或發展了早期先知書關於復興的預言(該二20~23;亞十二~十四,比較第八章;瑪四),表明這預言的完全應驗,仍然尚需等候。

《新約》

四部福音書都在一開始敍述耶穌事蹟時,明確地跟舊約聖經關聯上:《馬太福音》一開始就追溯耶穌的家譜至亞伯拉罕,點出大衛時期與被擄到巴比倫時期,都是家譜中的重要階段(太一1~17);《馬可福音》敍述了施洗約翰的到來,說這是「耶穌基督福音的起頭」,並將之與兩條預言復興的經文聯繫在一起(可一1~4;參見瑪三1;賽四十3);《路加福音》在描述施洗約翰和耶穌出世時說,此乃顯示了上帝對以色列的信實(路一46~55、67~79,二29~32);《約翰福音》則與創世記1章相呼應(約一1~9)。

耶穌在呼召人悔改時,是在「上帝的國近了」這個前提下發出呼籲的(太四17;可一15),這似乎與舊約聖經中上帝統治萬國的思想一脈相承(例如詩九十六~九十九),也與上帝赦免以色列並恢復他們民族命運的思想(例如賽四十1~11;耶卅一34;番三14~20)一脈相承。舊約對以色列復興的預言是否會在耶穌身上應驗呢?或許如此,但絕不會是簡單意義上的應驗。

耶穌似乎不斷在否定這樣的一種想法,就是上帝的國的來臨,一定會包括以色列國被重新恢復到她在萬族中享有顯赫地位的狀態。耶穌的訓誨與行事,都可以說是在評擊那種以民族主義的思想來詮釋上帝的國的做法:祂強調要以非暴力的方式使這國降臨(太五5、7、9);祂教人要愛仇敵(太五43-48),而這種對仇敵的愛,甚至要伸展到對羅馬的兵丁也要寬厚對待(太五41);祂對一些基於強烈民族主義聖潔觀的習俗提出質疑(守安息日的習俗,可二23~27;潔淨儀式,可七1~23),以及祂選擇跟那些被公認為不能得著這種聖潔的人在一起(路五27~32);祂猛烈評擊某些猶太人的宗教領袖,說他們將百姓引入歧途(太廿三1~32);祂攻擊聖殿(太廿一12~17),即那個整個猶太民族生活的中心,或許甚至還暗示了,錫安山將要被廢除作為上帝「聖山」的特殊地位(太廿一21~22;比較詩四十六~四十八);祂預言審判將必臨到耶路撒冷(路廿一5~24),而這場審判必會讓聖殿化為廢墟(5~6節)。所以祂後來被處死也是一件不足為奇的事。

然而,耶穌的行為也是與祂所說的上帝的國近了的言論一致:祂不禁食,暗示以色列的厄運結束了(可二18~22;比較亞八18~19);祂赦免人,這也與以色列的復興有關(可二1~12);祂呼召十二門徒,意味著以色列(所有十二支派)圍繞著祂而得到復興;祂醫病救人,有一處地方甚至說,這是神蹟,要表明被擄的情形就要告終了(太十一2~6;比較賽卅五章,特別參見5~6節)。最後,祂承認祂就是那位應許要來的彌賽亞,雖說祂只是私下對十二個門徒說,並且立刻補充到,祂很快會受死(可八27~33)。在祂人生後段所說的一句話,似乎暗示了,祂視祂自己的角色跟《以賽亞書》所說的那位僕人的角色相仿(可十45;比較《使徒行傳》八26~35;彼前二24~25),以此來解釋祂即將受死這件事。

耶穌的復活,出乎意料地證明了祂先前所說的一切都是真的。祂透過自己的復活,向眾人宣告,祂就是彌賽亞(徒二22~36,四8~11;比較羅一3~4)。就像《以賽亞書》所說的那個僕人一樣,祂也是背負了祂百姓的罪孽,且從死亡的另一端再度複現出來(參見賽五十三5-6、11~12),藉此,祂就使以色列的救贖得到了保障(路廿四17~27;徒三17~26),開通了救恩的道路(徒四12,五31),且展開了對整個創造界的更新(徒三21;林後五17)。

耶穌在復活後向眾門徒顯現,差遣他們,叫他們從耶路撒冷開始,奉祂的名將這悔改與赦罪的福音傳給萬民(太廿八18~20;路廿四47~48;徒一8)。當耶穌在離開他們回到父那裏去的時候,祂告訴眾門徒,祂還會再回來(徒一9~11);這一盼望在新約聖經的其他部分裏不斷迴響著(徒十七31;羅十三11~14;帖前四13~五10;來九27~28)。就這樣,早期教會就透過使徒的傳道開始被建立起來,從耶路撒冷遍及地中海一帶,直至《使徒行傳》的結尾部分,保羅到了羅馬去傳講耶穌的信息(徒廿八31)。

在《使徒行傳》中對早期教會之建立的敍述,也發展且更新了一些舊約聖經的思想。「使萬民作我的門徒……凡我所吩咐你們的,都教訓他們遵守」(太廿八18~19;比較羅一5),這項吩咐乃延續了上帝在錫安作萬國之王的思想。聖靈在五旬節降臨,讓許多民族的人都得以聽到救恩的信息(徒二1~11),應驗了《約珥書》有關「主的日子」的預言(二28~2),也反轉了巴別塔事件的咒詛(創十一1~9),應驗了上帝對亞伯拉罕的應許(創十二1~3),製造出了一個可能性,就是萬族聚集在一起,但是是來承認而不是來質疑上帝的王權(比較啟七9~10)。

眾使徒醫病,乃延續了耶穌對人的醫治(徒三1~10,五15~16,十四8~10,十九11~12):兩者都象徵著一種「能夠傳染人」的新聖潔,而這種聖潔是向外發散的,不像《利未記》所描述的那樣,會經常受到罪的威脅的。與這種聖潔直接相關的一點,就是非猶太人,現在也歡迎他們加入教會了,他們也能領受聖靈的恩賜(徒十1 ~十一18;參見弗二11~13);對非猶太人的接納與對舊約聖經聖潔觀的更新,這兩者間的關聯,在彼得接見羅馬百夫長哥尼流之前所看到的異象那裏表達得最明確。上帝在彼得的異象裏宣佈,那些代表外邦人的不潔淨動物都是「潔淨的」(十13~15、28)。保羅在寫給哥林多和以弗所那些摻入了外邦人的教會的書信時,把他們集體稱作「上帝的殿」(林前三16~17;弗二19~22;比較約二19~22;彼前二4~8),這一稱呼,不禁讓人對舊約的聖殿有更含義深遠的認識:上帝居住在哥林多的基督徒裏(參見王上八10~11),他們就是上帝治理萬國的居所(比較詩四十七8),萬國要透過他們來到上帝面前(比較賽五六7)。

然而,到了《使徒行傳》結束時,耶穌差遣門徒,要他們為萬民施洗,使萬民成為門徒的任務,還遠遠沒有完成。後期的書信更談到,教會裏有人走偏,追隨錯誤的教導(提前一3~11;提後三1~9;猶3 – 4;啟二14~6、20~25),很像約書亞時代之後,轉向敬拜偶像的以色列民。顯然,新約即將結束時,教會的故事尚未結束,甚至那不可能是故事的結尾。

但新約聖經的最後一卷書卻描繪了一個異象,就是在人類歷史結束時,上帝的仇敵最終會被擊敗(啟十九~二十),上帝和「羔羊」(耶穌)在「新耶路撒冷城」作王,這新耶路撒冷城就是新天新地的一部分(啟廿一~廿二)。在這城裏有一道「生命水的河」和一棵「生命樹」(啟廿二1-2),這就讓人想起了創世記一開頭所描述的情形(創二8~14)。

正如這些河流、樹木在城中的出現會使人想起創世記,這個人類的創造(參見創四17),也讓人想到後來人類的歷史,但現在人類歷史已被提升到全新的創造中了。新約所響起的最後一個音符,則是期盼與渴望主耶穌回來的音符(啟廿二12~21)。

Biblical History

by P. E. Satterthwaite

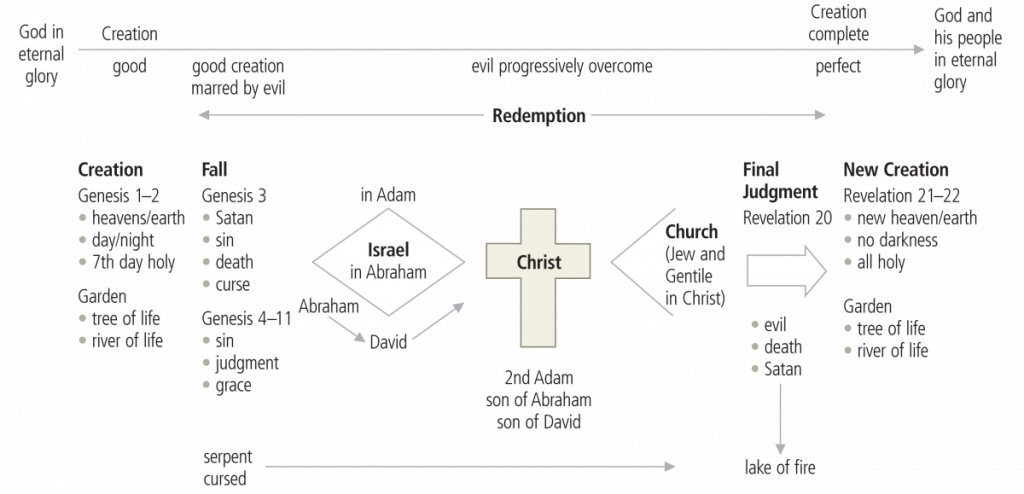

From creation to new creation

The OT begins by describing God’s creation of the world, all living creatures and, in particular, the first man and woman, who are blessed by God and charged with ruling the world in obedience to him (Gen. 1–2). Genesis 3–11 describe the disobedience of the man and the woman and its consequences, finishing in Genesis 11:1–9 with a picture of a world very like that of today, one in which men and women are alienated from God and each other and unable to remedy their circumstances.

But the account of the spread of humanity does not focus simply on the spread of human wickedness; God’s promise to the first woman (Gen. 3:15) suggests that her descendants will include ‘offspring’ (‘seed’: the term is ambiguous as to whether an individual or many descendants are in view) who will undo the destructive consequences of wickedness, and the genealogies of Genesis 3–11 pick up this promise by focusing on a particular line of descendants, from Adam through Seth, Noah and Shem, who are associated with hope, righteousness and blessing (Gen. 4:25–26; 5:29; 6:9; 9:26–27). A further genealogy takes this line down to Abram (Gen. 11:10–26).

In Genesis 12 Abram is called to leave his land and is given a promise of descendants who will become a great nation; they will not only enjoy God’s blessing but also be the means of bringing blessing to ‘all peoples on earth’ (vv. 2–3). The terms of this promise imply a reversal of the negative developments described in Genesis 3–11: a man whose descendants will restore the blessing promised to the first man (*cf. Gen. 1:28); a nation which will be used by God to address the plight of the scattered nations (cf. Gen. 11:1–9). Genesis 3–11 and 12 thus relate to each other as ‘problem’ and ‘answer’. The rest of the Pentateuch traces the partial fulfilment of this promise (D. J. A. Clines, The Theme of the Pentateuch [Sheffield, 1978]).

Abram’s descendants become a multitude in Egypt (Exod. 1:6–7), are rescued from oppression in the Exodus, and, through Moses’ mediation, enter into a covenant with God at Sinai, becoming a special nation, God’s people Israel, who will acknowledge his kingship by obeying his laws, mirroring his holiness in their corporate life, and thereby acting as priests, revealing God’s character to the nations and bringing blessing to them (Exod. 19:4–6; 20–23; Lev. 19:1–2; cf. Deut. 26:17–19).

Israel’s special relationship with God is reflected in their portrait in Exodus-Numbers; God is in their midst when they camp, and goes before them as they travel to the land he has promised them. By the time Moses addresses his last words to Israel in Deuteronomy, they are on the point of entering the land (Deut. 4:1–2; cf. Gen. 15:18–21).

The process of occupying the land begins under Joshua (Josh. 1–12). After problems in the land in subsequent generations (Judg., esp. 2:6–3:6), the conquest of the land is completed by David, Israel’s second king, when he captures Jerusalem (2 Sam. 5:6–10).

Since his reign sees the fulfilment of many of the promises given to Abraham, it is fitting that David should receive a promise concerning a line of rulers who would descend from him, the terms of which echo the earlier promises (2 Sam. 7:9–16, esp. v. 12; cf. Gen. 12:7; 15:4).

During the reigns of David and Solomon Israel enjoys the ‘rest’ in the land anticipated by Moses (2 Sam. 7:1; 1 Kgs. 5:3–4; cf. Deut. 12:10); God’s rule over Israel is made manifest by the bringing up of the ark to Jerusalem (2 Sam. 6) and the building of a temple there (1 Kgs. 6–8); and Israel starts to attract the admiring attention of the nations around her, again as Moses had hoped (2 Sam. 8:8–9; 1 Kgs. 5:1–2, 7; 10:1–9; cf. Deut. 4:5–8).

From this point, the figure of the Davidic king (for whom another title is ‘Messiah’ or ‘Anointed One’; cf. 1 Sam. 2:10) becomes important. Various texts in the Psalms, for example, develop the significance of the king’s role, linking it to the theme of God ruling the nations justly from Zion (see below).

There follows a long period of decline: the division of the kingdom under Solomon’s son Rehoboam, as a result of Solomon’s unfaithfulness (1 Kgs. 11–12); the growing disobedience of both northern and southern kingdoms (1 Kgs. 16; 2 Kgs., esp. 16, 21; Hos. 4–5; Jer. 2–3); the outworking of the covenant curses (Deut. 28) against both kingdoms through enemy invasion (1 Kgs. 14:25–26; 2 Kgs. 5:1–2; 10:32–33; 15:29; 24:1–2), siege and famine (2 Kgs. 6:24–25; 17:5; 25:1–3); and finally exile to Assyria and Babylonia respectively (2 Kgs. 17:6–23; 25:11). The Jerusalem temple is destroyed, God’s glory having already departed from it because of the defilement of the people (2 Kgs. 25:9; Ezek. 8–10).

The prophetic books which record warnings of coming judgment also contain prophecies of restoration after judgment: of God pardoning his repentant people (Hos. 2; Jer. 31:18–20; cf. Deut. 30:1–10; 1 Kgs. 8:46–51); of the two kingdoms reunited in a purified land (Is. 11:11–16; Jer. 3:18; 30:1–11; Ezek. 37:15–23; 48:1–29) and enabled to obey God in a new way (Jer. 31:31–34; Ezek. 11:16–21; Zeph. 3:9–13); of Jerusalem and the temple rebuilt (Is. 54; Jer. 33:1–13; Ezek. 40–43) and God dwelling once again in the temple (Ezek. 43:1–4; 48:30–35); of a king from David’s line who will rule the people justly (Hos. 3:5; Is. 11:1–9; Mic. 5:1–5; Jer. 23:1–6; Ezek. 37:24–28); of the nations coming to Zion to learn the ways of Israel’s God (Is. 2:1–4; Jer. 3:17); and ultimately of a restored creation, as in Ezekiel’s vision of a river flowing from the temple to revive the waters of the Dead Sea (47:1–12), or Isaiah’s vision of a new heaven and new earth (65:17–25).

Israel’s restoration is sometimes described (metaphorically) in what appears to be resurrection language (Ezek. 37:1–14; cf. Hos. 6:1–3). It is important to stress that Israel’s restoration is seen as part of a larger picture, the renewing of creation and the blessing of the nations, in fulfilment of God’s purposes in calling Abraham.

One of the most extended restoration prophecies, Isaiah 40–55, introduces an individual described as ‘[the Lord’s] Servant’ (Is. 42:1; 49:5–6), who in some sense takes over the role of Israel (also denoted by the term ‘servant’ in these chapters: 41:8–10; 45:4), that of witnessing to God’s power (43:10–13), when Israel in the misery of exile is too weak or stubborn to fulfil it (42:18–25; 48:1–11). This idea is especially clear in 49:3–6, where, speaking in the first person, the Servant declares that God said to him, ‘You are my servant Israel’ (v. 3), and that his appointed role is both to minister to Israel in exile (v. 5) and to be a ‘light to the nations’ (v. 6). In the most astonishing passage concerning the Servant, he is said, in language reminiscent of the Levitical sacrificial texts, to die for the sins of God’s people (53:5–6, 8, 11–12). The identity of this figure is uncertain, and not only because he is unnamed. In some respects he resembles a king or prophet, and he also shares a number of features with Moses, particularly Moses as portrayed in Numbers. However, his role is essentially unprecedented. The time-frame of Isaiah 49–55 is also unclear; these chapters seem to look beyond the return from exile to a time when Zion’s glory will be fully restored (ch. 54), and the Servant’s ministry and death may be located in this distant future

The books of Ezra and Nehemiah record what actually happened next: that Cyrus king of Persia, having defeated Babylon, permitted the exiles from the southern kingdom and their descendants to return to Judah (Ezra 1:1–4); that many of them did so, rebuilt the temple and celebrated the Passover in Judah again (Ezra 3; 6:13–22); that under Nehemiah the walls of Jerusalem were rebuilt in the face of opposition (Neh. 3–4, 6); that Jerusalem was re-inhabited (Neh. 11) and the walls dedicated with great joy (Neh. 12:27–43). These are significant achievements, yet a note of longing and disappointment is also sounded in these books. At the heart of the ceremonies described in Nehemiah 8–10 there is a long prayer of confession (ch. 9), which concludes with the Israelites lamenting their present situation; they remain slaves in the land God gave to their forefathers (v. 36), subject to foreign kings and ‘in great distress’ (v. 37). The books of Ezra and Nehemiah both conclude with chapters describing the sins into which some of the returned exiles fell: Sabbath violations (Neh. 13:15–22); failure to provide tithes (Neh. 13:10–13); and, most seriously, marriages with non-Israelite wives (Ezra 9–10; Neh. 13:23–28). It is clear that the events described in Ezra and Nehemiah fall well short of the hopes expressed by the ‘restoration’ prophecies.

Each of the post-exilic prophetic books concludes with passages which, in different ways, restate or develop the earlier prophecies of restoration (Hag. 2:20–23; Zech. 12–14, cf. ch. 8; Mal. 4), indicating that a complete fulfilment is still awaited.

The New Testament

All four Gospels begin their accounts of Jesus with clear backward links to the OT: Matthew by tracing Jesus’ genealogy back to Abraham, highlighting David and the Babylonian exile as significant stages in the genealogy (Matt. 1:1–17); Mark by relating John the Baptist’s coming, which he sees as ‘the beginning of the gospel about Jesus Christ’, to two prophetic restoration texts (Mark 1:1–4; cf. Mal: 3:1; Is. 40:3); Luke by presenting the births of John the Baptist and of Jesus as a demonstration of God’s faithfulness to Israel (Luke 1:46–55, 67–79; 2:29–32); John by echoing Genesis 1 (John 1:1–9).

Jesus’ call for repentance in the light of the coming of the kingdom of God (Matt. 4:17; Mark 1:15) seems similarly to pick up OT ideas of God’s rule over the nations (*e.g. Pss. 96–99) and God’s forgiving Israel and restoring their fortunes (*e.g. Is. 40:1–11; Jer. 31:34; Zeph. 3:14–20). Are the OT prophecies of Israel’s restoration to be fulfilled in Jesus? Perhaps so, but not in any straightforward sense.

Jesus seems consistently to repudiate the idea that God’s coming kingdom will include Israel’s being restored to a position of pre-eminence among the nations. His teaching and actions can be seen as an attack on nationalistic views of the kingdom: his emphasis on non-violent ways of bringing in the kingdom (Matt. 5:5, 7, 9); his teaching of love for enemies (Matt. 5:43–48), which extends even to generous behaviour towards Roman soldiers (Matt. 5:41); his calling into question practices which are based on a strongly nationalistic view of holiness (Sabbath observance, Mark 2:23–27; ceremonial purity, Mark 7:1–23), and his association with those commonly held not to share in this holiness (Luke 5:27–32). He fiercely criticizes the Jewish religious leaders for leading their people astray (Matt. 23:1–32). He attacks the temple (Matt. 21:12–17), the centre of the nation’s life, and perhaps even hints at the abolition of Mt Zion’s special status as God’s ‘holy mountain’ (Matt. 21:21–22; cf. Pss. 46–48). He prophesies the coming of judgment upon Jerusalem (Luke 21:5–24), which will leave the temple a ruin (vv. 5–6). It is hardly surprising that he is executed.

Yet Jesus’ actions are consistent with his claim that the kingdom of God is at hand: his avoidance of fasting, implying that Israel’s misfortunes are over (Mark 2:18–22; cf. Zech. 8:18–19); his dispensing of forgiveness, also related to Israel’s restoration (Mark 2:1–12); his calling of twelve disciples, with its implication that Jesus is restoring Israel (all twelve tribes) around himself; the healings, at one point presented as signs that the exile is at last coming to an end (Matt. 11:2–6; cf. Is. 35, esp. vv. 5–6). Finally, he acknowledges that he is the promised Messiah, though only privately to the Twelve, and with the immediate qualification that he is going to die (Mark 8:27–33). A later saying seems to imply that he understands his role as similar to that of the Servant in Isaiah (Mark 10:45; cf. Acts 8:26–35; 1 Pet. 2:24–25), and thus points to his coming death.

Jesus’ resurrection is the unexpected vindication of his claims, the event by which he is publicly declared to be the Messiah (Acts 2:22–36; 4:8–11; cf. Rom. 1:3–4). Like the Servant in Isaiah, Jesus takes his people’s sins on his own shoulders and emerges on the other side of death (*cf. Is. 53:5–6, 11–12). He thus secures Israel’s redemption (Luke 24:17–27; Acts 3:17–26), opens the way of salvation (Acts 4:12; 5:31) and begins the renewal of the entire creation (Acts 3:21; 2 Cor. 5:17).

Appearing to his disciples after his resurrection, Jesus charges them to take the message of repentance and forgiveness in his name to all nations, beginning at Jerusalem (Matt. 28:18–20; Luke 24:47–48; Acts 1:8). When Jesus leaves them to go to the Father, his disciples are told that he will return (Acts 1:9–11); this hope is echoed in other parts of the NT (Acts 17:31; Rom. 13:11–14; 1 Thess. 4:13–5:10; Heb. 9:27–28). Thus the early church comes into being through the apostles’ preaching, spreading out from Jerusalem around the Mediterranean world, until at the end of Acts Paul is preaching the message of Jesus in Rome (Acts 28:31).

In the account of the early church in Acts several OT ideas are developed and transformed. The command to ‘make disciples of all nations … teaching them to obey everything I have commanded you’ (Matt. 28:18–19; cf. Rom. 1:5) takes up the idea of God ruling over the nations from Zion. The coming of God’s Spirit at Pentecost, enabling people from many nations to hear the message of salvation (Acts 2:1–11), fulfils Joel’s prophecy of the Day of the Lord (2:28–32); it is also a reversal of the Tower of Babel incident (Gen. 11:1–9) and a fulfilment of the promise to Abraham (Gen. 12:1–3), creating the possibility of people from many nations joining together to acknowledge, rather than to contest, God’s kingship (*cf. Rev. 7:9–10).

The apostles’ healings continue those of Jesus (Acts 3:1–10; 5:15–16; 14:8–10; 19:11–12): both are signs of a new, ‘contagious’ holiness which works outwards rather than, like the holiness described in Leviticus, being constantly under threat from sin. Clearly linked to this holiness is the welcoming of Gentiles into the church, and their endowment with the Holy Spirit (Acts 10:1–11:18; cf. Eph. 2:11–13); the link between Gentile inclusion and the transformation of OT ideas of holiness is made explicit in Peter’s vision before he meets the Roman centurion Cornelius, in which unclean animals, representing Gentiles, are declared ‘clean’ by God (10:13–15, 28). Paul, writing to partly Gentile churches in Corinth and Ephesus, declares them collectively to be ‘God’s temple’ (1 Cor. 3:16–17; Eph. 2:19–22; cf. John 2:19–22; 1 Pet. 2:4–8), a designation which, given the OT associations of the temple, has far-reaching implications: the Corinthian Christians are indwelt by God (*cf. 1 Kgs. 8:10–11); they are the locus of God’s rule over the nations (*cf. Ps. 47:8); it is through them that the nations can approach God (*cf. Is. 56:7).

By the end of Acts, Jesus’ charge to baptize and make disciples of all nations is far from accomplished. The later letters speak of some in the churches turning aside to false teaching (1 Tim. 1:3–11; 2 Tim. 3:1–9; Jude 3–4; Rev. 2:14–16, 20–25), rather as the Israelites in the generations after Joshua turned to idolatry. It is clear as the NT draws to a close that the story of the church is not over, or even necessarily close to its end.

But the last book of the NT presents a vision in which, at the close of human history, the enemies of God are finally defeated (Rev. 19–20), and God and ‘the Lamb’ (Jesus) reign in a ‘new Jerusalem’ which is part of a renewed heaven and earth (Rev. 21–22).

The presence in the city of ‘the river of the water of life’ and ‘the tree of life’ (22:1–2) recalls the beginning of the biblical account (Gen. 2:8–14), just as their presence in a city, a human creation (*cf. Gen. 4:17) recalls subsequent human history, now taken up into the new creation. The last note sounded in the NT is one of expectation and longing for the return of the Lord Jesus (Rev. 22:12–21).

另參:

如何用三千字總結舊約聖經?(TGC)

五分鐘介紹舊約聖經(唐宏階)

One thought on “聖經中記載的歷史(NDBT)”